Author: Kiyana Rahimian

Over half a century ago, the first internal organ transplant took place. A seminal kidney transplant marked the start of years using organ transplants as a means to treat diseased and injured organs. As years progress, the population of older individuals who are more susceptible to organ failure increases. This worsens the shortage of organ donors we are already experiencing.8 Even without a shortage, an organ transplant surgery comes with the possibility that the transplanted organ is rejected. Transplant patients have to continue using immunosuppressant medication, which has many complications, to reduce the risk of rejection later in life.8

Developing tissue engineering materials and techniques may help reduce and eliminate risks associated with the treatment associated with diseased organs. Tissue engineering is an emerging area in biomedical engineering and a major component of regenerative medicine. The term tissue engineering refers to the process of assembling functional tissues by combining cells, scaffolds, and biologically active molecules.8 It provides the ability to generate biological substitutes that can restore and maintain function for therapeutic applications.3

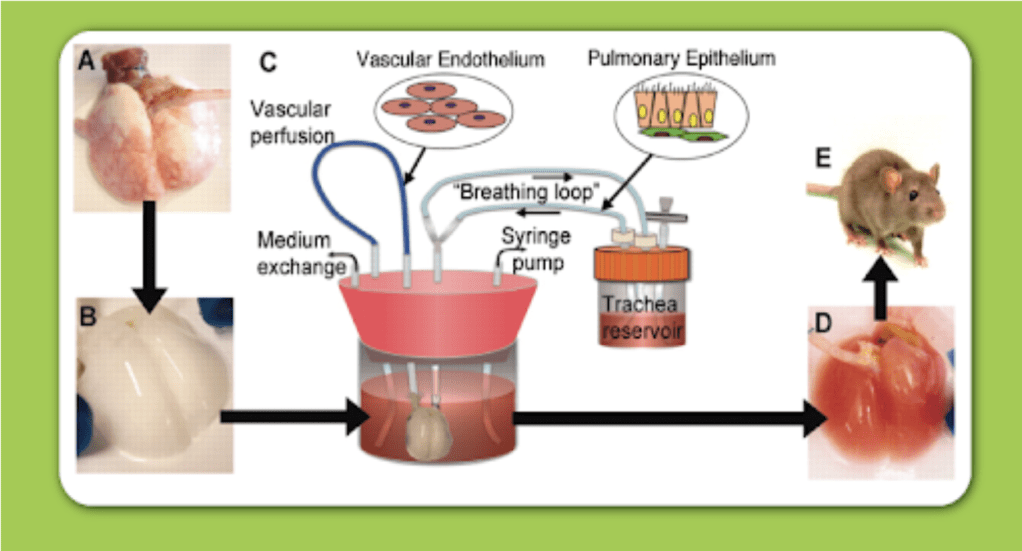

There exist two subcategories of tissue engineering; Ex vivo tissue engineering and in situ tissue engineering. Ex vivo is a process that involves stem cells from the donor, or patient to be seeded onto a scaffold, and for their proliferation and differentiation to be stimulated to form the desired tissue. The process takes place in a suitable environment provided by a bioreactor (see Figure 1).2 The cells and engineered tissue grown onto the scaffold are placed into the patient.

Figure 1. Diagram illustrating how bioreactors can provide a suitable environment for tissue culture growth and tissue harvesting.11

In contrast, In situ tissue engineering involves cell and tissue growth to only takes place in the actual body. The In situ process involves the pre-fabrication scaffold being implanted onto the required tissue. The implementation of the acellular scaffold attracts the host’s cells and promotes their proliferation and tissue regeneration.6 The only purpose of the scaffold is to help orient the new tissue growth. In both cases, over time after the implementation, the scaffold degrades to provide room for freshly regenerated tissues.2

The best scaffold for engineering tissue needs to have features analogous to the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the target tissue (Figure 2).1,8-9 The extracellular cellular matrix serves as natural scaffolding for tissues in the body.4 The solid ECM is composed predominating of collagen and elastin which are insoluble structural proteins.1 To be analogous, they need to use certain biomaterials. Previously, due to the lack of understanding of the ECM, diseased tissues or parts were replaced by synthetic material that would provide structural support like tetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) and silicone. Now that more knowledge has been gained regarding the ECM interactions with biological components, better choices can be made regarding the materials used.8

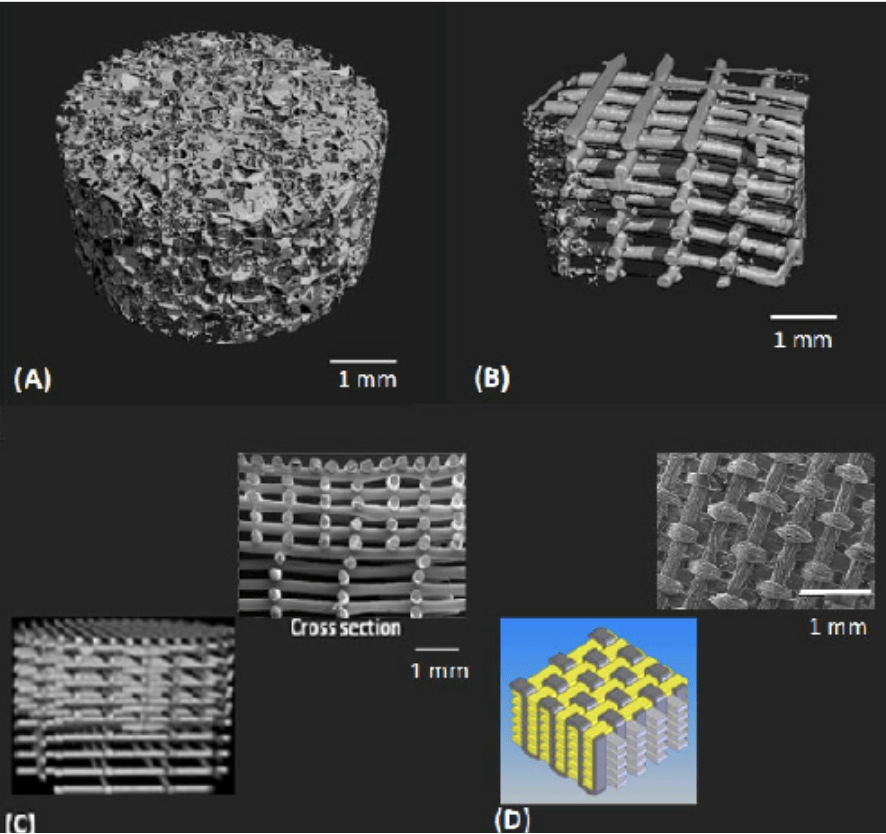

Biomaterials used for scaffolds should be porous enough to facilitate nutrient and metabolite transport but still have mechanical stability. Biomaterials used also need to be compatible with the engineered tissue cellular components as they need to support growth and differentiation processes of either extraneously applied or endogenous cells.1 Most animal cells are anchorage-dependent, meaning they will not survive if they are unable to anchor onto a substrate, so they require cell-adhesion substrates.9 Thus, not only do they need to be compatible, biomaterials in tissue engineering need to provide this substrate. Additionally, the biomaterial must be biodegradable to prevent interference with new tissue growth in the long term.8 Typically, naturally derived tissues like collagen, acellular tissue matrices such as small intestinal submucosal, or synthetic polymer have been used to bioengineer the scaffold.9

Figure 2. Examples of various scaffold designs for cartilage tissue engineering.5

Currently, applying tissue engineering to patients’ treatments is limited since it is still experimental and developing them is very costly. One present issue with tissue engineering is that engineered tissues bigger than 200 microns do not have vascular networks to exchange nutrients and waste with cells and hence are unable to survive. Researchers are trying to implement vascular systems in engineered tissues. In fact, a NIBIB researcher is trying to overcome this limitation by developing a sugar solution lattice that hardens. The goal is for tissues to develop around the lattice and dissolve once blood is added leaving channels that imitate blood vessels.10

This goes to show that tissue engineering is still experimental. Its development is very costly and so its application in real current treatment is very limited. The FDA has however approved the use of certain engineered tissues such as cartilage and artificial skin. Examples of engineered tissues that have been implemented in patients include skin grafts and supplemental bladders. One of the most impressive to date however is the use of engineered tissue to develop a full trachea and implement it in patients.7 So although tissue engineering is currently limited, it is emerging as a transformative force in medicine offering personified therapeutic applications. It continues to illuminate a path towards revolutionary breakthroughs in regenerative medicine.

Bibliography

- Chan BP, Leong KW. Scaffolding in tissue engineering: general approaches and tissue-specific considerations. Eur Spine J. 2008 Dec;17(S4):467–79.

- Eldeeb AE, Salah S, Elkasabgy NA. Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications and Current Updates in the Field: A Comprehensive Review. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2022 Sep 26;23(7):267.

- Di Silvio L. Bone tissue engineering and biomineralization. In: Tissue Engineering Using Ceramics and Polymers [Internet]. Elsevier; 2007 [cited 2024 Feb 21]. p. 319–31. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9781845691769500150

- Godfrey M. Extracellular Matrix. In: Asthma and COPD [Internet]. Elsevier; 2009 [cited 2024 Feb 21]. p. 265–74. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780123740014000225

- Izadifar Z, Chen X, Kulyk W. Strategic Design and Fabrication of Engineered Scaffolds for Articular Cartilage Repair. JFB. 2012 Nov 14;3(4):799–838.

- Koh CJ, Atala A. Tissue Engineering, Stem Cells, and Cloning: Opportunities for Regenerative Medicine. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2004 May;15(5):1113–25.

- Li M, Li J. Biodegradation behavior of silk biomaterials. In: Silk Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine [Internet]. Elsevier; 2014 [cited 2024 Feb 21]. p. 330–48. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780857096999500124

- Olson JL, Atala A, Yoo JJ. Tissue Engineering: Current Strategies and Future Directions. Chonnam Med J. 2011;47(1):1.

- Xing H, Lee H, Luo L, Kyriakides TR. Extracellular matrix-derived biomaterials in engineering cell function. Biotechnology Advances. 2020 Sep;42:107421.

- Arnaud CH. Sugar Scaffold Templates Blood Vessels. Chemical & Engineering News [Internet]. 2012 Jul 9 [cited 2024 Feb 21];90(28). Available from: https://cen.acs.org/articles/90/i28/Sugar-Scaffold-Templates-Blood-Vessels.html

- Whaley Products Inc. Information about Bioreactors and growing Human Tissue [Internet]. Bioreactor Chillers. 2016 [cited 2024 Feb 21]. Available from: http://bioreactorchiller.com/human-tissue-and-science/

Leave a comment