Author: Muhammad Siddiqui

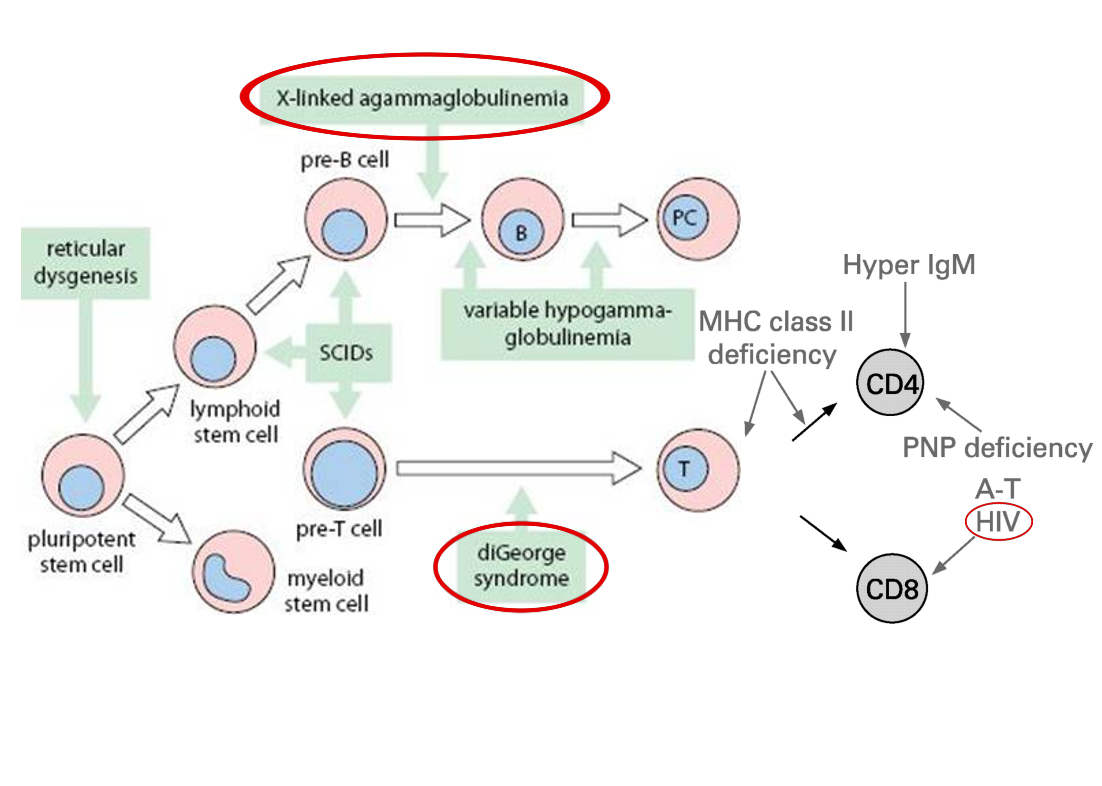

Immunodeficiency is a broad term that results in the failure or absence of elements in the immune system (1). As a result, individuals are often more susceptible to infections and diseases, leading to adverse health outcomes. There are two main types of immunodeficiency: primary and secondary. Primary refers to inherited genetic immunodeficiencies, such as X-linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA) and DiGeorge Syndrome (1). Secondary refers to immunodeficiencies caused by disease, medication, or environmental factors. The most well-known secondary immunodeficiency is HIV/AIDS, as it was once a potent and highly stigmatized disease. Today, the advancements in understanding and treating immunodeficiency have drastically increased the lifespan of those with these health issues. This article outlines the current treatment for some of the more potent and well-known immunodeficiencies, such as XLA, DiGeorge syndrome, and HIV/AIDS (see Figure 1).

Many of you may not have heard of X-linked Agammaglobulinemia, XLA, but it is a relatively common primary immunodeficiency affecting 5-10 million people worldwide (2). XLA is an inherited immune disorder characterized by the inability of B cells to make antibodies (3). As stated in the name, XLA is X-linked, meaning an X chromosome mutation exists. The X chromosome’s mutated genes in XLA code for a protein known as Bruton tyrosine kinase, BTK (3). This immune disease is recessive, signifying that males are at a higher risk of developing XLA as they only need to inherit one mutated X chromosome with the BTK gene. The symptoms of XLA include increased severity and frequency of throat, nose, and ear infections, as individuals cannot make antibodies against these diseases to form a proper immune response. Additionally, those with XLA cannot produce antibodies, so they will not benefit from vaccination (3). The standard treatment for those with XLA is through replacement antibodies and prophylactic antibiotics to prevent any infections from occurring (4). Patients are given these antibodies through injection either in the veins intravenously every 1-14 days or through their skin subcutaneously every 2-4 weeks (4). However, this treatment has many side effects, as the body would react negatively against the antibodies injected, leading to further adverse health outcomes. Novel treatment methods, such as targeted antibody treatment for specific diseases, are currently being investigated. One is undergoing clinical trials using IgG antibodies in those with XLA to treat pneumonia (4). It has been found that injection of 100 mg/dL of IgG resulted in a 27% decrease in the incidence of pneumonia in those with XLA (4). This promising treatment still needs to undergo more rigorous evaluation, but it is a promising breakthrough in immunodeficiency treatments.

The subsequent immunodeficiency that I would like to discuss is DiGeorge syndrome. Similar to XLA, DiGeorge syndrome is an inherited disease. It is one of the most common microdeletion syndromes in humans, affecting one in every 3000-6000 people (5). These microdeletions are of 1.5-3 million base pairs on the long arm of chromosome 22 (5). The key symptoms of DiGeorge disease are both mental and physical. Some key mental symptoms include an increased risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), schizophrenia, and anxiety (5). At the same time, some physical symptoms include heart abnormalities, gastrointestinal abnormalities, seizures, and immunodeficiencies (5). Those with DiGeorge disease are at an increased risk of developing immunodeficiencies, as almost 75% of patients report this (5). As DiGeorge symptoms are quite broad, this is reflected in its treatments. To minimize the effect of psychiatric conditions, those with DiGeorge are often prescribed anti-anxiety medications such as sertraline and trazodone, along with strategies to curb their anxiety (5). Meanwhile, the most practical and effective treatment for physical symptoms is surgery for the various issues caused by DiGeorge.

The final and most well-known immunodeficient that this article describes is the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HIV is a retroviral infection that severely weakens one’s immune system and is often the precursor to acquired immune-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) (6). HIV/AIDS is one of the most potent diseases in the world, as it is the sixth leading cause of death worldwide (6). HIV is often diagnosed through a blood test examining the amount of CD4, a key T cell in the adaptive immune response. Those with HIV often have low counts of CD4 in their blood. The earlier the diagnosis of HIV, the more effective the treatments are. As a result of the mortality, longevity, and publicity of HIV/AIDS, there have been significant strides made in the biotechnology sector in finding a cure for this disease. A newly approved drug for HIV treatment is Lenacapvir, which works by inhibiting the HIV caspid protein, a key structural protein of the HIV virion, within infected individuals (7). By targeting this capsid protein, lencapavir interferes with the virion’s early and late life cycle by interrupting nuclear transport, virus assembly and release, and capsid assembly (7). Lenacapvir is also able to bind in a space in between HIV capsid proteins, leading to abnormalities in its structure (7). This is a new treatment for HIV, and its effectiveness is still being determined. The approval of this drug sets the stage for not only other HIV drugs but immunodeficiencies more broadly, as through funding and awareness, it is possible to cure even the most potent immunodeficiencies.

Figure 1. Adapted flowchart of B-cell and t-cell development in the adaptive immune system, indicating stages where development or function are impacted by common primary and secondary immune deficiencies. XLA, diGeorge Syndrome, and HIV are circled in red. SCID: severe combined immune deficiency; PNP; purine nucleoside phosphorylase; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; BM: bone marrow; A-T and HIV infection affect mature T cells (8).

Works Cited

1. Justiz Vaillant AA, Qurie A. Immunodeficiency. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 18]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500027/

2. X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) – Immunodeficiency UK [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.immunodeficiencyuk.org/x-linked-agammaglobulinemia-xla/

3. X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA) | NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/x-linked-agammaglobulinemia

4. El-Sayed ZA, Abramova I, Aldave JC, Al-Herz W, Bezrodnik L, Boukari R, et al. X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA): Phenotype, diagnosis, and therapeutic challenges around the world. World Allergy Organ J. 2019 Mar 22;12(3):100018.

5. Kraus C, Vanicek T, Weidenauer A, Khanaqa T, Stamenkovic M, Lanzenberger R, et al. DiGeorge syndrome. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2018;130(7):283–7.

6. Rumbwere Dube BN, Marshall TP, Ryan RP, Omonijo M. Predictors of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in primary care among adults living in developed countries: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2018 Jun 2;7(1):82.

7. Lenacapavir (HIV prevention) – Health Professional | NIH [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 18]. Available from: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/drugs/lenacapavir-hiv-prevention/health-professional

8. Edgar JD. T cell immunodeficiency. J Clin Pathol. 2008 Sep;61(9):988–93.

Leave a comment